Making Ireland Great Again

Cheering for loyalists and the coming harmonisation of Irish nationalism

Last week saw five nights of rioting across Loyalist areas following the horrific sexual assault of a young girl by two Romanian boys in Ballymena. The rioting, which supposedly initially targeted the homes of the accused, quickly morphed into an anti-immigrant pogrom, with houses being torched or having their windows smashed across the town. Immigrants in the affected areas hastily put Ulster Banners and Union Jack stickers in hopes that the Loyalist angel of arson would pass peacefully by their front door. Over the next few days, unrest spread to other Loyalist strongholds in Larne, Portadown, Derry, and Newtonabbey, with a community centre burned and dozens of PSNI officers injured.

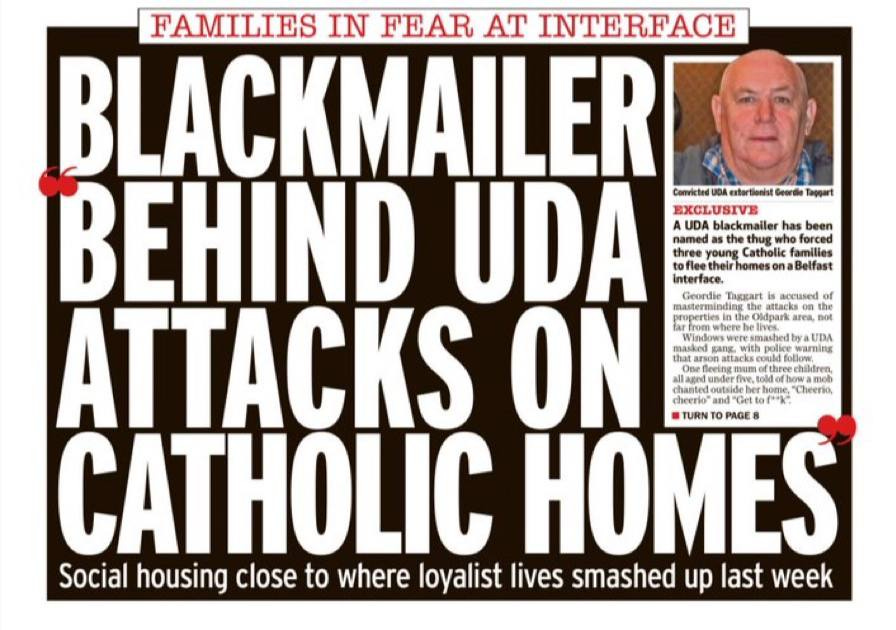

Loyalist rioting is nothing new; being something that happens almost every summer. Even house-burnings and pogroms are nothing new, with five Catholic families forced out of their homes as recently as May. What was new was the level of support the rioting received from the Free State’s new right-wing online.

A surprising number of the clips of last week’s violence were narrated with southern accents, and Free State X accounts predictably masturbated to the prospect of the wave of arson escalating. Numerous Irish right-wing influencers seem hellbent on portraying Loyalist thugs as a sort of long-lost ‘brothers in arms’ — ignoring the fact that waving a tricolour anywhere near the mobs in Ballymena and beyond would have quickly turned the crowd on them. Conversely, loyalism seems happy to embrace the Free State’s anti-immigration right as ‘the good ones’ whilst labelling their nationalist neighbours as leftwing extremists and ‘plastic paddies’. A hatred of Sinn Fein and Socialist Republicanism is something shared by both loyalist and Free State chuds alike — making ideologies, that at first glance seem at odds, palatable to each other.

The danger here is that a new strain of Irish nationalism is being synthesised, one detached from Republican principles, such as language and national unity, and willing to see staunch opponents of those things as friends. This little-Englander nationalism is unknowingly — or perhaps knowingly in some cases — doing Britain’s work for it, casting the only mainstream party pushing Irish reunification as traitors, Republican groups of all stripes as fringe radicals, Loyalists as comrades, whilst constructing a cargo-cult identity from the same brand of Irishness you’d find in an airport giftshop.

It’s plain to see that Irish society is now locked in an increasingly hot ‘culture war’ — America’s most significant contemporary export. On one side, we have an increasingly active right-wing movement that has emerged in several working-class communities in Dublin, egged on by a constellation of foreign right-wing influencers and accounts that continually further their narrative, whilst injecting Trumpism, Zionism and English nationalism. On the other side, we have a loose confederation of Republicans, liberal academics, students, and activists, too often tongue-tied by American campus moralism to organise an effective opposition. Both sides see each other as caricatures, be it Bohs jersey-wearing leftist nerds or knuckledragging fascist ‘scrotes’.

In effect, Irish nationalism has had its head separated from its body. A dwindling and compromised Republican movement, toothless trade unions, and an increasingly distant Sinn Féin have severed the link between working-class heartlands and republican politics. One of the driving factors behind the rise of this new nationalism is that many involved have a strong sense of patriotism with no clear politics, often being completely politically disengaged on every issue except immigration. People who, years ago, would’ve found a home in Republicanism are now increasingly drawn into the anti-immigration movement.

The reasons for this are varied, but the two main ones are that for-profit IPAS centres in the south are being placed in small and struggling communities without consultation and a deluge of foreign and domestic far-right content is being continuously pushed by social media algorithms, creating a sense of constant imminent threat. High-profile crimes committed by immigrants in this tinder-dry environment serve as a spark that ignites everything, proving people’s worst fears and driving them onto the streets.

Internationally, this recurrent violence in Ireland has turned into a spectacle, with online grifters and faceless accounts projecting the image of a violent and no-nonsense Irish that their people should imitate, usually with little knowledge or care for the dynamics or cultural divides already present on the island. Conversely, the immigration issue has paralysed an increasingly gentrified Republican left, unable to find the words to defuse the multidimensional issue created by the Dublin and Westminster governments, before being dropped like a bomb on their communities. However, without a Republican position on immigration, not to mention a strong presence in affected communities and on the algorithm, the floor is effectively open for the right to run away with Irish nationalism. Left to them, Irish nationalism will soon mean little more than throwing shapes with an ‘Erin Go Bragh’ flag or getting a selfie at the Black Forge Inn.

A collapse of traditional republicanism would be a blessing to both London and Dublin, removing the most significant threat to the status quo and replacing it with a malleable and shallow rump nationalism — the kind that sings Ireland’s call and blushes for rampaging loyalists. This sort of movement could be easily managed with a carrot and a stick: Cracking down on ugly episodes of unrest with extreme prejudice and then drip-feeding immigration reform when growth slows down, following the blueprint of the British Labour Party. In this terrain, calls for an Irish Republic would grow quieter, and the language of Republicanism would fade from the nationalist vernacular, replaced with a standard-issue Western populist right that runs on the meaningless and imported maxims about making Ireland great again.

Lots of good points here, two more I would add are - this harmony between hardline right CNR and PUL has been in existence much earlier than recent times. When it comes to issues like abortion rights, even in the height of the Troubles, both sides were able to put aside their hatred of one another and work together to ensure this island remained abortion free.

There's also a lot to be said too about Big House unionism purposefully whipping up racist sentiments and young Loyalist men (who feel they have been sold out by a peace process they were not included in) heeding the cause, and being sent out to destroy communities, sowing division and keeping Big House unionism in power. It's a tale as old as time.

Conversely, Republicans in power have lost their grip on the right wingers within their faction - illustrated in an electoral sense with the splitting off of Aontú from SF. So you're right that these right winger Republicans are becoming "little Englanders" and moving away from the traditional values of Irish Republicanism.

But the biggest question here for me is, what are the "traditional values" of Irish Republicanism? And maybe we have always been rooted in seeking whiteness - which explains why these disgraceful anti-immigrant views have been allowed to grow. The roots were already there.

The recent article, '‘No race hate here’? Irish national identity and racism in the mid twentieth century' by Jack Crangle is particularly illuminating, particularly Section 4:

"Irish nationalist identity was predicated on an exclusionary, white conception of nationhood. In the late nineteenth century, Ireland's burgeoning home rule movement flourished partially through cultivating a distinctive form of cultural nationalism through arenas such as sport, literature, dress, language and music. Institutions such as the Gaelic Athletic Association were constructed to actively distinguish Irish cultural practices from those of Britain, asserting a coherent cultural identity to accompany political nationalism. Central to this ‘Gaelic revival’ was the notion that the Irish were a discernible ‘race’, one that should be rooted in its own sovereign territory. This belief in cultural and racial distinctiveness informed Ireland's post-independence nation-building project, culminating in a state crafted around an identity that, excluded ethnic minorities due to its reliance on ‘ethnic belonging’ and ‘historic ties to place’. Independent Ireland, therefore, emerged with a ‘new-found sense of whiteness’ in which racial specificity was actively asserted and championed."

https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/irish-historical-studies/article/no-race-hate-here-irish-national-identity-and-racism-in-the-mid-twentieth-century/38314DBEDB338A76E46DE416EDF9493C

didn’t know you were on Substack!